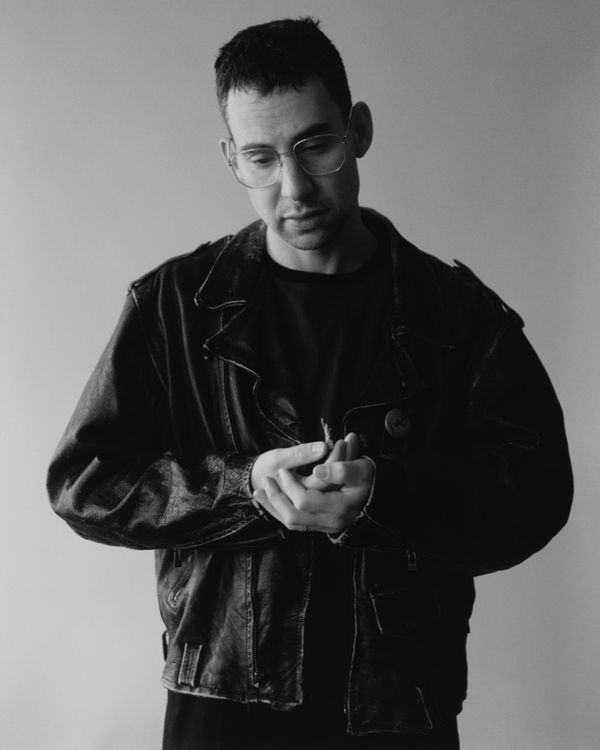

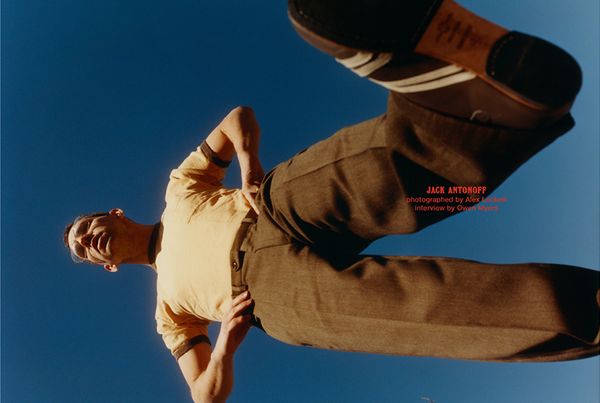

Styling by Patricia Villirillo

Jack Antonoff’s recording HQ at Electric Lady Studios in New York isn’t so much a studio space as a Tardis-like expanse, crammed with analogue gear decked with dials and knobs to confuse any time traveller. The airy, light-flooded room has been a hub for the Grammy winning artist, producer and multi-instrumentalist for about a decade. He’s recorded genre-spanning albums here with Taylor Swift, Lana Del Rey, St. Vincent, Clairo, Lorde and The Chicks, among others, and it’s where he laid down the tracks for the latest record from his Springsteen-indebted punchy pop band, Bleachers.

“Everything’s so documented in the world, but up here it feels very protected,” he says, seated on a squishy couch on a crisp spring morning. “With people who are recognisable and make things in public, it’s like the world is a reality show. It’s a huge exhale up here because it’s a protected space. No one’s gonna go [on Instagram] Live out of nowhere. Or if they did, it would be really funny.”

As well as working on Swift’s upcoming release, The Tortured Poets Department – which, as I’m reminded by his team, he won’t be speaking about today – Antonoff has just released his fourth album as Bleachers, a self-titled work featuring muscular, arena-sized rock ’n’ roll cut with a wry humour. It also includes perhaps his prettiest song to date, ‘Tiny Moves’, a swooning tribute to his wife, the actress Margaret Qualley. It’s a subtle reminder of the range that has helped canonise Antonoff, a guy who still reps the New Jersey punk scene that made him.

My favourite song on the new record is ‘Call Me After Midnight’, which you worked on with Kevin Abstract and Ryan Beatty.

Kevin is brilliant. And Ryan Beatty is one of the great artists of our time that a lot of people are just discovering. Whenever you get in a room with him… you’re a believer. One of the special sounds on the track is the M1 piano, this really janky piano sound. It’s the sound that I use on Lorde’s ‘Green Light’, when it switches. It’s a dancey, UK sound.

Because there’s so much of it here in your studio, I’ve been thinking about the gear you use – specifically that synth that goes in and out on ‘Self Respect’.

That’s actually a guitar. Sometimes I get my best ideas when I try to make something sound like something else. I read this thing a long time ago from a great guitarist – I think it was John Scofield – who said that his biggest influence was Coltrane. It makes so much sense. Why would your biggest influence be someone that does the same thing? Often I’ll have my greatest ideas for songs when I’m looking at a building.

In post-punk and new wave, all the synths sounded like guitars.

Yeah, like Suicide. I’m interested in how you can make a familiar thing feel unfamiliar. Sometimes you just get so gassed on how you did something that it feels like a fun secret to you. On ‘Self Respect’, I actually call out a piece of gear: “The Binsons go vroom and the Bastards go yawn.” The Binson is this old, really beautiful echo machine I use a lot. And they rev up and make these crazy sounds, and they’re all over the album. And so I liked the duality of [the phrase]. That’s me vibrating on the general failure of imagination around me towards people who aren’t my actual fans.

What do you mean by failure of imagination?

That song’s a lot about that. Florence wrote the lyric, “I’m so tired of having self-respect.”

Because it would be easier if you didn’t?

We’re obsessed with projecting a certain kind of opinion, or self-respect. And the insane black-and-white-ness of either toeing an exact line from the internet, or going full-blown fascist, is so inhuman. It’s actually boring and exhausting. I’m so tired of having to illustrate that I’m a decent person. It is, as Nick Cave says, morally obvious. You know, things that are morally obvious are important to comment on. There’s this line [which mentions] Kobe dying, Kendall’s Pepsi ad, my sister dying…” When I wrote it, it almost made me laugh because it felt so absurd. But that’s what it’s like to be a human being. When people are like, “I’m shattered by this,” and it’s like, “Yeah, but then you had lunch.” And then you go back to being shattered. My brain works in these patchworks. Even as I’m talking to you, I can’t stop thinking about my açaí bowl coming.

Are you wearing a hoodie from your old punk band Outline?

Yeah! One of my bandmates, Daniel, gave it to me. It was the greatest gift.

You said before that being in that band in the late 1990s made you fall in love with performing. What got you hooked?

I think it forces you to interact with the pieces of performing beyond just the sounds you’re making. Very often we played places with no sound systems. Very often the mics wouldn’t work, or you’d set up your amps and drums, and everyone would just have to turn up to be as loud as the drums in a hall. It’s fucking loud. It forces you to create a life around the show. I wasn’t raised as one of these people who is like, “What you hear coming out of this amp is the whole show.”

Do you think that starting out in punk gave you a kind of ethos that you still hold on to?

It made me. And even with the “failure of imagination” comment I made, I find that because my work has reached different places, and because I can be somewhat unplaceable, that I’m often denied things that actually happened. It’s hard for people to imagine that I came from the New Jersey punk scene. Because it wouldn’t really make sense that one would go from there to pop music, or that Bleachers could carry that spirit I grew up with. But that’s what it was. I had this weird upbringing where it was very fast. It was the late 1990s, early 2000s New Jersey punk scene. Lifetime is breaking up and the Brunswick scene is melding into this new thing where bands like Saves the Day are starting.

You rep New Jersey to the extent that a couple of years ago, you partnered with a local pizzeria on a Bleachers tomato sauce.

I think a lot about where an artist is reporting from. To me, Randy Newman’s reporting from LA, Outkast’s reporting from Atlanta. I’ve always felt like, literally, I was reporting from New Jersey. But there’s a weird blend between the classic Jersey sound of E Street and Southside Johnny, and the sound I grew up with, like Lifetime and Saves the Day. It’s a torch I really want to travel around the world with.

Your recent song ‘Alma Mater’ features Lana Del Rey. Did that grow out of your other work with her?

We were just fucking around. The bones of that song, and the recording, are us messing around in the studio. I wanted it to feel like you were in the studio with us, so I left a lot of those loose bits.

Its looseness reminds me of the more casual and impressionistic moments on Lana’s album Did You Know That There’s a Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd. How do you bottle that informal feeling?

It’s not difficult in concept. The simple answer is that you take the moments that are in the room. [When recording] I’m searching for a feeling I can imagine, and then I know it when I hear it. And this is obviously a remarkable oversimplification, but that really is all it is. I’m not interested in hearing anything overly perfect, unless it needs to be. I think what makes the albums [I work on] great, is recognising, “That’s what the band sounds like. That’s what the artist sounds like. That’s what I sound like.” And then protecting it. It’s why my world, I feel, stays pretty insular. These things are like a house of cards. If I was building a house of cards, I wouldn’t invite 30 people over to help me build it. I think a lot of records die by committee. I call it answer shopping.

Answer shopping?

Yeah. It’s the dumbest thing you could do. If you were in therapy, you wouldn’t be like, “Please hold there. Let me call nine other people and see what they think.”

Do you think it’s changing? A decade ago, all the big pop songs were coming out of writing camps; now a lot of major artists are making music with just one producer. You and Taylor, Billie Eilish and Finneas, Olivia Rodrigo and Dan Nigro…

Yeah, maybe. I read an article where Dua was saying how she made an album with Kevin [Parker], and she was like, “We basically started a little band.” That’s so nice. That’s all it is. You get a group of people together, you all believe in something that feels impossible, and then you say, “No, we’re gonna do it.” I do think that’s becoming more in vogue, in the same way farm food is becoming fashionable. I think the writer camp is age-old, and there’s still tons of that, but I do feel a looseness from… has anyone ever said Big Music, like how people say Big Tech? I feel a looseness from Big Music that excites me. But it’s probably for a cynical reason, which is just that it costs the industry nothing any more, because they don’t have to promote records. Everything just exists.

The Grammys was a big night for you this year, with your three-peat of receiving Producer and Album of the Year for Midnights. What is it like to be in that room and to be so recognised?

It’s so fucking weird. It’s insane. Cameras everywhere. Everyone’s dolled up. I felt a little protected because it was me, Margaret, Taylor and Lana. Actual close friends of mine. My best interactions were with SZA’s mom and Tony Bennett’s son.

The other people who were like, “Why am I here”?

Yeah. It’s a strange environment. It’s funny to be very successful at something and also feel very outside of it. Sometimes I think there’s this impression of me that I would know everyone, but I really don’t. It’s a pretty small amount of things that I do, and I dig deep with certain people. So I do feel a little at-bat with myself versus the impression of me, versus just the literal hunger I feel from not eating all day at those things.

Do they let you have anything to eat? A Kind bar?

I brought in some stuff. There was a coughed-on charcuterie board that I wasn’t going to touch.

You’ve collaborated with Taylor Swift for almost a decade now. Has she changed how you think about music?

All my collaborators – her, everyone I’ve ever made an album with, my family, my partner, the man sitting over there, a very small group of people on a daily basis – are changing how I see my art, the world, everything. I’m very community oriented, and I think the way that you can speak to the world is to speak to your community; chuck it out there like a message in a bottle, and see if anyone agrees.

If you could be a fly on the wall during the recording of any album throughout history, which record would it be?

Tom Waits’s Bone Machine. It sounds crazy. There’s mythology that he played a marimba made of human bones. I don’t know if that’s true. It was made in the studio called Prairie Sound, which I got to work out of later. There’s all these pipes and things. Apparently, Waits banged on all of them. I’d love to see a lot of the great records being made, but that record just sounds so insane. It’s very frightening, and it interests me because it doesn’t sound like anything that I know how to do.

TEAM CREDITS

Grooming: Kevin Ryan

Set Design: Joonie Jang

Miniature Set Artist: Jon Frier

Location: Electric Lady Studios

Creative Production: Zion Studios

Executive Producer: Sara Zion

Production Manager: Jennifer Urbanowski

Photo Assistant: Isaac Schell

Styling Assistant: Maddie Wexler

STYLING CREDITS

All clothes from Jack’s personal archive sourced by Patricia Villirillo; shoes throughout from Zeha Berlin.